Introduction

Haemorrhoids are a condition where the blood vessels, muscle fibres and connective tissue in the anal canal below the dentate line prolapse or slide out of place. They are also known as piles. Many people in our population use the term ‘piles’ to describe any anal symptoms.

Some factors of modern life that may contribute to haemorrhoids are eating more processed foods, leading a sedentary lifestyle, and using cell phones while defecating, which means spending more time on the toilet.

There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that there are regional variations in the incidence of haemorrhoid disease. These variations tend to correlate closely with social development indices. Improving social parameters and economy in the old Mysore region may be coinciding with the increasing incidence of the disease. This is primarily linked to dietary patterns and consumption of processed foods with tends to increase with affluence.

The main symptom of haemorrhoids is painless rectal bleeding.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of haemorrhoids is based on history and physical examination rather than laboratory tests or imaging studies. The usual symptom is painless rectal bleeding during or after bowel movements, which may appear as bright red blood on the toilet paper or on the stool surface. Severe itching and anal discomfort are also common, especially with chronic haemorrhoids.

Clinical History

A thorough patient history is important. It should include the extent, severity and duration of symptoms, frequency of bowel movements, other symptoms (eg, constipation, faecal incontinence), daily dietary habits, and details of bowel movements (eg, time spent during each bowel movement and use of cell phone).

Regarding bowel habits, some patients may have chronic constipation or diarrhoea. Therefore, what a patient considers a normal bowel habit may not be normal and should be investigated. It is also important to rule out other conditions that can cause anal symptoms, such as external thrombosed haemorrhoids, anal fissures, anal abscesses and Crohn’s disease.

Clinical Examination

A digital rectal examination is the next step. A specialist colorectal surgeon will check for skin tags, sphincter tone, perianal hygiene and other anal lesions. They will also look for any signs of colorectal cancer on the digital rectal examination.

Endoscopy

Since rectal bleeding can be a symptom of several diseases, including colorectal cancer, a colorectal surgeon will review any previous endoscopic results. Patients who have a high risk of colon cancer should ideally undergo rigid proctoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

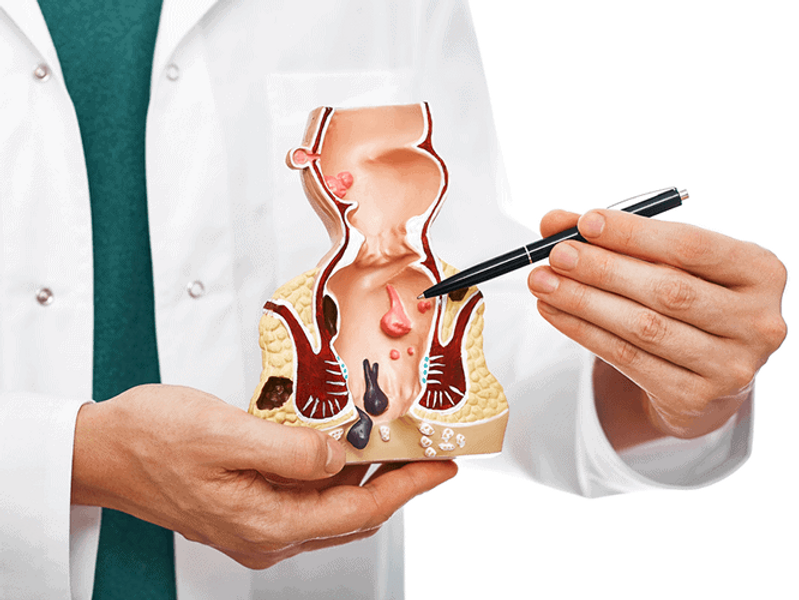

Grades

Haemorrhoids are classified into four grades according to their severity. Grade I is the least severe and grade IV is the most severe. Treatments that can be done in the office are effective for grade I, II and some grade III haemorrhoids. Surgical excision is the standard treatment for high-grade haemorrhoids.

Range of treatments

The choice of treatment for haemorrhoids depends on several factors, such as the grade and severity of the disease, its impact on the quality of life, the degree of pain it causes, the patient’s compliance with treatment and the patient’s personal preference.

The treatment usually starts with a high-fibre diet and other lifestyle changes that include bowel movement behaviours. Colorectal surgeons spend a lot of time educating patients about these aspects regardless of the type or severity of the disease.

Treatments can be divided into three categories: conservative, clinic-based and surgical.

Conservative management

Conservative measures aim to soften the stool, relieve pain and correct bad toileting habits. In most cases, lifestyle is the main factor that triggers haemorrhoids and unless patients change it they are more likely to have recurrent symptoms in the long term.

No mobile in the bathroom

People take their phones into the bathroom and this habit is blamed for increasing the time on the toilet and leading to increased pressure on the anal region and straining during defecation. Some research suggests a direct link between the time spent on the toilet and hemorrhoidal disease Garg and Singh use the acronym “TONE” to remind patients of appropriate defecation habits:

Three minutes for defecation

Once-daily defecation

Enough fibre

One way to prevent and treat haemorrhoids is to increase the fibre intake. Fibre helps to soften the stool by drawing water into the colon, which reduces the pressure and strain on the anal canal. The recommended daily fibre intake is about 28 g for women and 38 g for men, which can be achieved by eating more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. Psyllium husk is a natural fibre supplement that can be added to the diet to boost the fibre intake.

Laxatives: A Complementary Treatment

Another option for haemorrhoid relief is to use laxatives, which are medications that stimulate bowel movements or change the consistency of the stool. Laxatives are usually reserved for cases where there is an underlying bowel problem rather than a dietary issue. They can also be used in combination with fibre supplements to enhance their effect. However, laxatives should not be used for a long time or without medical supervision, as they can cause dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, or dependence.

Other Options: Topical Anaesthesia

Some people may find relief from applying topical anaesthetics to the affected area, which can numb the pain and itching caused by low-grade haemorrhoids. However, there is no reliable evidence to support the effectiveness or safety of this method. Moreover, topical anaesthetics may cause allergic reactions or skin irritation in some people.

Clinic-Based Treatments: Minimally Invasive Procedures

For haemorrhoids that do not respond to conservative management, there are several clinic-based treatments that can be performed by trained colorectal surgeons. These treatments are minimally invasive procedures that aim to reduce the blood flow to the haemorrhoidal tissue, causing it to shrink and eventually fall off. These treatments are suitable for grade I, II, and III haemorrhoids that protrude from the anus. They can be done without any anaesthetic or bowel preparation, and they have lower complication rates than surgery. The most common clinic-based treatments are:

Rubber band ligation: This involves placing a rubber band around the base of the haemorrhoid, cutting off its blood supply and causing it to necrose and detach. This is an excellent option for grade II haemorrhoids, as it is easy to perform, has low pain scores, and can treat recurrences.

Infrared photocoagulation: This involves using an infrared probe to produce heat that coagulates and destroys the haemorrhoidal tissue.

Sclerotherapy: This involves injecting a sclerosing agent into the haemorrhoid, which triggers an inflammatory reaction and forms scar tissue that blocks the blood supply to the haemorrhoid.

Surgical management:

For patients with severe or recurrent haemorrhoids that do not respond to other treatments, surgery may be the only option. Surgery is the most effective and definitive treatment for haemorrhoids, as it removes the haemorrhoidal tissue completely. However, surgery also has higher risks of complications, such as bleeding, infection, pain, incontinence, or recurrence. Therefore, surgery should be reserved for patients with high-grade internal haemorrhoids (grades III and IV), external or mixed haemorrhoids, or complicated haemorrhoids (such as thrombosed or strangulated ones). The most popular surgical options are:

Excisional haemorrhoidectomy: This involves cutting out the haemorrhoid with a scalpel or scissors. This is the most conventional surgical technique, and it has the lowest recurrence rate. However, it also has the highest pain scores and recovery time.

Doppler-guided hemorrhoidal artery ligation: This involves using a Doppler probe to locate and tie off the arteries that supply blood to the haemorrhoid. This reduces the blood flow to the haemorrhoid and causes it to shrink over time.

Stapled haemorrhoidopexy: This involves using a stapling device to lift up and fixate the prolapsed internal haemorrhoid back into its normal position. This reduces the pressure on the haemorrhoid and improves its blood supply.

Laser haemorrhoidectomy: This involves using a laser beam to vaporise or cauterise the haemorrhoid. This reduces bleeding and swelling of the haemorrhoid.

Individualised Treatment is Key

There is no single best treatment for haemorrhoids. Each patient is unique and has different preferences, expectations, and medical conditions. Therefore, a colorectal surgeon and the patient should work together to find the most suitable treatment option for each case. They should weigh the pros and cons of each treatment option and consider factors such as effectiveness, safety, cost, availability, convenience, and quality of life.

Acknowledgement:

Turgut Bora Cengiz, MD and Emre Gorgun, MD, FACS, FASCRSCleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine September 2019, 86 (9) 612-620; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.86a.18079

Author

Dr Nikhil Nanjappa M.S., FRCS Ed., M.IPD Ed., M. FST Ed., has recently returned from the United Kingdom after serving as a Consultant Surgeon at St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds. He is a consultant surgical gastroenterologist and a colorectal surgeon. He is amongst only a handful of surgeons in the country with 3 years of super speciality training experience in colorectal surgery. He has extensive experience and is trained in advanced minimally invasive techniques for the management of haemorrhoids, fissures and fistulas.

For appointments visit www.drnikhilnanjappa.com or call +91081 27867